|

Case Report

A rare case of pancreatic mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma

1 Hospitalist, Internal Medicine, ThedaCare Regional Medical Center, Appleton, Wisconsin, USA

2 Hematologist and Oncologist, Cumberland Medical Center, Crossville, Tennessee, USA

Address correspondence to:

Faraz A

TN,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100138Z10ZK2024

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Zhou K, Faraz A, Hendrixson M. A rare case of pancreatic mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Case Rep Images Oncology 2024;10(2):26–30.ABSTRACT

Pancreatic mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma (pMANEC) is an extremely rare malignancy with both acinar carcinomas with neuroendocrine lineage differentiations. Herein, we present a case of pMANEC in a 78-year-old male who initially presented to the clinic for night sweats, easy bruising, and lumbar pain, leading to the discovery of a pancreatic mass on imaging. Pathological examinations, including immunohistochemistry, confirmed the diagnosis of possible pMANEC, characterized by acinar and neuroendocrine differentiation. Further diagnostic workup with DOTATATE NM positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan provided additional insights, confirming the neuroendocrine nature of the tumor. The patient was started on gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel every other week and also started on lanreotide for treatment. Our case highlights the challenges in diagnosing and managing this rare entity and underscores the need for further research to explore its clinical behavior, molecular characteristics, and optimal therapeutic strategies. Additionally, the potential role of genetic profiling and immunotherapy in improving outcomes for patients with pMANEC warrants investigation.

Keywords: Acinar cancer, Cancer, Mixed acinar neuroendocrine cancer, Neuroendocrine cancer, Pancreas, Pancreatic cancer

Introduction

Pancreatic cancers are divided into exocrine (common) and endocrine (uncommon) cancers. Exocrine cancers typically consist of ductal and acinar cancers of the pancreas. Most pancreatic cancers are pancreatic ductal carcinomas; whereas acinar carcinomas of the pancreas are relatively rare (approximately 1% of all exocrine pancreatic neoplasms) [1]. In contrast to pancreatic ductal carcinomas, acinar carcinomas of the pancreas produce exocrine enzymes and exhibit unique histologic characteristics and immunohistochemistry properties [2]. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms commonly referred to as pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (pNENs) are the most common endocrine neoplasm of the pancreas. However, they account for only 1–2% of all pancreatic neoplasms [3]. Pancreatic mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma (pMANEC) defines a group of acinar carcinomas with neuroendocrine lineage differentiations. Pancreatic mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma accounts for 15–20% of all acinar cell carcinomas [4], making it an extremely rare type of cancer with an annual incidence of less than 0.01/100,000 and only 96 patients alive with this diagnosis in the whole world [5].

The diagnosis of pMANEC requires clinical suspicion, pathological evaluation, and immunohistochemical staining. The clinical features of pMANEC depend on the tumor grade, site of metastasis (lymph node, liver, and/or other distant organs), and the tumor size. These features are largely variable. The mean age of pMANEC presentation is 68 years old and patients with pMANEC usually have an advanced pT classification, prevalent lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and lymph node and distant metastases [6]. Pathological features of pMANEC include highly cellular acinar components without significant fibrous stroma and devoid entirely of desmoplasia with = 30% of the cells exhibiting neuroendocrine marker (chromogranin and synaptophysin) expressions [5]. Recent studies indicate that TP53, BRAF, KRAS, and microsatellite instability are potential drivers of pMANEC [5]. Similar to the clinicopathological course of acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas, pMANECs have a poor prognosis with a high recurrence rate [6]. As such, pMANEC is usually treated with the standard of care for pancreatic adenocarcinomas of the same site of origin, which includes radical surgical resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy for localized disease and platinum-based chemotherapy for extensive or metastatic cases [5].

Mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma remains a rare and underrecognized entity; further research studies are required to explore its clinical characteristics and treatment options. Here we present a case of pMANEC which will add to the literature and contribute to our understanding of pMANEC.

Case Report

A 78-year-old Caucasian male with a significant past medical history of hyperlipidemia, vitamin D deficiency, spinal stenosis of the lumbar region, and chronic kidney disease stage 3 presented to the primary care physician’s office with the chief complaint of night sweats, easy bruising, chronic lumbar pain, and intermittent claudication of bilateral lower extremities for 2–3 months. He had a smoking history of 20 years and quit about two years ago. His family history was significant for prostate and bladder cancer in his father.

His vital signs were within normal limits. He had some right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness but an otherwise unremarkable physical exam. Initial basic laboratory workups included complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, serum amylase, serum lipase, and lactate dehydrogenase. The results were noticeable for white blood count 10,200 cells/uL, hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, and platelet 218,000; whereas serum transaminase, lipase, amylase, and lactate dehydrogenase were within normal limits during his visits. Iron studies revealed elevated ferritin 1149 (normal range 30–400 ng/mL), total iron binding capacity (TIBC) 136 (262–474 mcg/dL), unsaturated iron binding capacity 111 (normal range 111–343 mcg/dL), iron 25 (76–198 mcg/dL), iron saturation 18% (normal range 60–170 mcg/dL), erythropoietin 32.6 (normal range 2.6–18.5 mU/L), reticulocyte count 2.1% (normal range 0.5–1.5%).

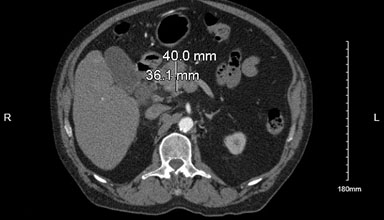

Due to the claudication symptoms in the lower extremities, computed tomography angiography (CTA) aorto-iliofemoral runoff was performed, which showed a 4 cm × 3.6 cm mass in the pancreatic head with significant celiac and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy, significant common iliac artery, and distal superficial femoral artery stenosis on the right side, relatively mild stenosis on left lower extremity arteries, and a hyper-vascular lesion in the right hepatic lobe (Figure 1).

The patient was referred to an oncologist for pancreatic mass seen on the CTA abdomen and pelvis. Tumor marker assays were checked and showed elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) 1789 ng/mL (normal range 0–8.5 ng/mL), carcino-embryogenic antigen (CEA) 2.1 ng/mL (normal 0–5 ng/mL), carbohydrate antigen 19.9–20 U/mL (normal range 0–37), chromogranin A 931.2 ng/mL (normal range 0–101.8 ng/mL), and serotonin 75 ng/mL (normal range 50–200 ng/mL).

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) was recommended by the oncologist and the FNA biopsy was obtained. The pathology of the FNA biopsy of the pancreatic mass was positive for malignancy, revealing neoplastic cells in rosettes, and scattered single cells with moderate eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and occasional nucleoli. An immunohistochemical examination showed positive AE1/3, BCL-10, and trypsin; negative MUC 1 and CD 56, with focal and weak labeling for chromogranin and synaptophysin, and Ki67 at about 40%.

He subsequently underwent a Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET) scan that revealed a 4.7 cm hypermetabolic mass in the head of the pancreas with multiple hypermetabolic peripancreatic and portocaval lymph nodes (Figure 2).

DOTATATE NM PET/CT skull base to mid-thigh was obtained as suspicion arose of a combined acinar and neuroendocrine tumor in immunohistochemistry (IHC), and DOTATATE scan confirmed it with DOTATATE uptake in the right supraclavicular node, superior mediastinal node, peripancreatic soft tissue mass, and mass/adenopathy near caudate lobe and celiac axis with intense uptake and the pancreatic neck mass without significant uptake (Figure 3).

The pathology findings combined with the DOTATATE scan confirm the MANEC nature of this pancreatic neoplasm. He was started on gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel every other week and also started on lanreotide for the neuroendocrine component. The patient responded effectively to the first round of chemotherapy; nevertheless, he had a spiking fever before the commencement of the second round, which was initially diagnosed as fever of undetermined origin (FUO). About two months after DOTATATE scan was obtained, he was admitted to the hospital for fever and a CT scan of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed many hepatic lesions, gallstones, and a pancreatic head and neck mass in addition to several enlarged and partially necrotic mediastinal and upper abdominal lymph nodes. His FUO differential diagnosis was considered to be necrotic lymph nodes as opposed to cholecystitis. He had a cholecystostomy, but the fever never went away, so levofloxacin was prescribed, and he was sent to a skilled nursing facility. His family chose to take comfort measures when his condition deteriorated, and he eventually passed away.

Discussion

Pancreatic mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma is a type of sporadic cancer; our understanding of pMANEC is limited to case reports and case series studies. Symptoms of pMANEC are determined by its location and invasion, if any. In the present case, although the troublesome lumbar pain and intermittent claudication of bilateral lower extremities were likely caused by peripheral artery disease, the significant celiac and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy around the same areas likely exacerbated the patient’s presentation. Our case study supports the general understanding of an advanced pT classification, prevalent lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and lymph node and distant metastases upon the diagnosis of pMANEC [6].

The diagnosis of pMANEC involves the gross features of the pancreatic biopsy pathology revealing both acinar and endocrine differentiations but not the common ductal components [7] . In the present case, pathology of the pMANEC demonstrated neoplastic cells in rosettes and scattered single cells with moderate eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and occasional nucleoli which are different from pancreatic duct histology.

The typical immunohistochemical profile of acinar cell carcinoma is positive for CK8 and CK18 (positive for AE1/AE3 labels), pancytokeratin, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and BCL-10. In contrast, the pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor is usually positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin. The present case immunohistochemical profile was positive for AE1/3, BCL-10, and trypsin with focal and weak labeling for chromogranin and synaptophysin [4],[7] . In IHC, pancreatic acinar carcinomas can also be positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin [7]. As a result, a DOTATATE NM PET/CT scan, which is the most sensitive exam in neuroendocrine tumors, was performed and revealed avid uptake in the tumors largely overlapping the regular CTA and PET/CT scan results. The results of the DOTATATE NM PET/CT scan thus were consistent with the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. The present case had a Ki67 at about 40%, which translates into poorly differentiated in the grading of neuroendocrine tumors.

Additional testing of neuroendocrine tumors includes serum chromogranin A and urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid [8],[9]; they are very sensitive tumor markers in neuroendocrine tumors. However, these markers can also be high in multiple other conditions. Not surprisingly, given the final diagnosis of pMANEC, the serum chromogranin A level was significantly elevated in this case, although regrettably, urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid was not checked in the present study. With the data mentioned above, the patient was eventually diagnosed with pMANEC.

Because of its rarity and the similar aggressiveness of the disease, pMANEC has been traditionally treated as its counterpart to pancreatic adenocarcinomas. In the present case, the patient was started on gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel with lanreotide (targeting the specific neuroendocrine components). The development of genetic profiling in oncogenes and microsatellite instability status may shed light on future research in pancreatic MANEC. For example, TP53, BRAF, KRAS, and microsatellite instability (MSI) were found to be potential drivers of pMANEC; their corresponding target therapies for these gene mutations and immunotherapies in correspondence with high microsatellite instability may provide additional treatment options. In the study of Milione (2018), TP53 mutation was present in 23.9%, KRAS in 16.9%, BRAF 5.6%, and MSI in 5% of the cases [5]. So far only two case reports have investigated genetic mutations in MANEC. The new modalities such as anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies may be considered for advanced MANEC with MSI-high. However, only two cases have investigated genetic mutations in MANEC therefore, further investigations are needed to completely understand the incidence and prognostic effects of genetic mutations in MANEC [10]. The median cancer specific survival of patients with pMANEC was estimated to be 41 months [11].

Conclusion

In conclusion, pMANEC is a rare type of cancer, and awareness of this entity is crucial for timely diagnosis and appropriate management. Its diagnosis requires composite information from pathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular profiling. Further disease-specific research is warranted to optimize treatment decisions and improve outcomes in patients with pMANEC.

REFERENCES

1.

Wisnoski NC, Townsend CM Jr, Nealon WH, Freeman JL, Riall TS. 672 Patients with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: A population-based comparison to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2008;144(2):141–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Klimstra DS, Adsay V. Acinar neoplasms of the pancreas—A summary of 25 years of research. Semin Diagn Pathol 2016;33(5):307–18. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, Grant CS, Petersen GM. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: Epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer 2008;15(2):409–27. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

La Rosa S, Adsay V, Albarello L, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 62 acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas: Insights into the morphology and immunophenotype and search for prognostic markers. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36(12):1782–95. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Frizziero M, Chakrabarty B, Nagy B, et al. Mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms: A systematic review of a controversial and underestimated diagnosis. J Clin Med 2020;9(1):273. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Kim JY, Brosnan-Cashman JA, Kim J, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas and mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinomas are more clinically aggressive than grade 1 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Pathology 2020;52(3):336–47. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Calimano-Ramirez LF, Daoud T, Gopireddy DR, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: A comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol 2022;28(40):5827–44. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Gkolfinopoulos S, Tsapakidis K, Papadimitriou K, Papamichael D, Kountourakis P. Chromogranin A as a valid marker in oncology: Clinical application or false hopes? World J Methodol 2017;7(1):9–15. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Wedin M, Mehta S, Angerås-Kraftling J, Wallin G, Daskalakis K. The role of serum 5-HIAA as a predictor of progression and an alternative to 24-h urine 5-hiaa in well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms. Biology (Basel) 2021;10(2):76. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Yoshino K, Kasai Y, Kurosawa M, Itami A, Takaori K. Mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma of the pancreas with positive for microsatellite instability: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep 2023;9(1):122. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Abdelrahman AM, Yin J, Alva-Ruiz R, et al. Mixed acinar neuroendocrine carcinoma of the pancreas: Comparative population-based epidemiology of a rare and fatal malignancy in The United States. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15(3):840. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Zhou K - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Faraz A - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Hendrixson M - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2024 Zhou K et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.