|

Case Report

The devolution of a mature plasma cell dyscrasia into a fatal plasmablastic lymphoma

1 DO, MSc, Resident, Internal Medicine, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, San Antonio, Texas, United States

2 MD, Resident, Pathology, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, San Antonio, Texas, United States

3 DO, Fellow, Hematology/Oncology, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, San Antonio, Texas, United States

4 MD, Attending, Pathology, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, San Antonio, Texas, United States

5 MD, Attending, Hematology/Oncology, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, San Antonio, Texas, United States

Address correspondence to:

Morgan P Pinto

DO, MSc, San Antonio, Texas,

United States

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100124Z10MP2023

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Pinto MP, Thorneloe NS, Brown MR, Stalons ML, Stoll KE, Holmes AR, Pathan M, Gonzales PA. The devolution of a mature plasma cell dyscrasia into a fatal plasmablastic lymphoma. J Case Rep Images Oncology 2023;9(2):7–14.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare, aggressive, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with an untreated prognosis as poor as three months. There exists scant literature describing transformation of plasmablastic lymphoma from a more benign dyscrasia, the mature plasmacytoma. This case report describes the transformation of plasmablastic lymphoma from a mature plasma cell neoplasm/plasma cell myeloma in an atypical combination of patient characteristics.

Case Report: A 66-year-old man presented with acute onset right lower extremity pain and rapidly progressive mobility loss. He was found to have a lytic lesion in the lateral right iliac wing. Biopsy revealed the lesion to be plasmablastic lymphoma with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) positivity by in situ hybridization with a Ki-67 proliferation index >99%, and strongly staining CD138 and MUM-1. CD20 and PAX-5 were negative. A bone marrow biopsy from the right iliac crest showed mature plasma cells without evidence of plasmablastic lymphoma cytology found in the initial specimen. These specimens showed CD138 positivity with 15–20% plasma cells with Kappa positive clonality by in situ hybridization, and diffusely Epstein–Barr virus negative by in situ hybridization. Further plasma cell fluorescence in situ hybridization study showed a clone with a TP53 deletion and an immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement that did not translocate to one of the common plasma cell dyscrasia translocation partners (FGFR3, CCND1, MAF, or MAFB). Additionally, a near-tetraploid subclone was observed in approximately 60% of nuclei. Also, there was gain of BCL2 gene or chromosome 18/18q, gain of BCL6 gene or chromosome 3/3q and MYC amplification. There was no MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements. Our patient was neither HIV-positive nor immunocompromised, rather Epstein–Barr virus positive with a quantitative polymerase chain reaction level greater than 67,000. He was started on Daratumumab combined with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone.

Conclusion: This case exhibits a unique presentation of plasmablastic lymphoma in terms of disease presentation, unique risk factors, including HIV-negativity and male-assigned sex, and the creativity of treatment utilized.

Keywords: Daratumumab, EPOCH, HIV negative, Plasmablastic lymphoma, Plasmacytoma

Introduction

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare, aggressive malignancy with an untreated prognosis of approximately three to four months, and has an incidence rate of PBL is approximated at about 2% of all HIV-related lymphomas [1],[2]. Plasmablastic lymphoma was first described in South African patients as a disease highly associated with HIV-positivity, with nearly universal involvement of the oral cavity [3]. Oral lesions have thereafter been a characteristic feature of PBL, with the addition of scattered, less common, extra-oral manifestations such as bone, skin, soft tissue, breast, mediastinum, heart and lungs [4]. Plasmablastic lymphoma has a predilection for HIV-positive males, with an approximately 75% preference over HIV-positive females in a comprehensive review of 260 PBL diagnoses from 1997 to 2014 [5]. As more data have been captured on this rare disease, it has been shown that PBL can also, although less commonly, arise in immunocompetent, HIV-negative patients. Interestingly, HIV-negativity shows the reverse patient preference, favoring females (34%) over males [1],[2]. In these cases, female patients tend to present with heterogeneous site involvement, although again with oral lesion predominance. Presumably due to degrees of immunocompromise, advanced stage disease (Ann Arbor stages III and IV) is more expected in HIV-positive patients, and less so in HIV-negative ones [5]. Only 25% of highly malignant cases in one comprehensive review arose in immunocompetent patients [1],[6],[7]. Thus, it is rare to see an immunocompetent HIV-negative male patient develop PBL. This case presents PBL that arose in a rare set of patient characteristics: an immunocompetent, HIV-negative male with predominantly bone involvement and severe, stage IV disease.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is considered a sub-set of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, with an EBV-based proliferation mechanism. Its pathogenesis is associated with a combination of MYC over-expression and EBV co-infection. The proposed pathogenesis of PBL involves pre-disposition to dysregulated cellular proliferation secondary to MYC-oncogene translocation and rearrangements in the setting of EBV infectivity and prevention of apoptosis. Immunocompromised individuals do not have the ability to clear EBV affected cells leading to the development of malignancy [1],[5]. Positivity for EBV RNA expression positivity (EBER positivity) is therefore a strong marker of disease development, and as we suppose it is also disease prognosis. In one study, approximately of 70% of diagnosed cases were EBER positive; most of these patients were additionally HIV-positive [8].

In the rarest of cases, which encompasses the patient presented herein, PBL can transform from another hematologic dyscrasia [1]. Transformed PBL (as seen in our patient from a mature plasma cell neoplasm) is extremely uncommon, and, as of recently, only determined to be secondary to either chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or follicular lymphoma (FL) [1]. There have been scant reports of transformed PBL in the literature. Castillo’s review from 1997 to 2014 reported a total of 11 cases, again arising from CLL or FL. Speculation has arisen as to the relationship between plasmablastic lymphoma and the more benign dyscrasia, the mature plasmacytoma. Such investigations have largely returned less than reassuring toward a defined relationship between a mature plasmacytoma and plasmablastic lymphoma. Additional features of plasmacytoma, that would be expected in the setting of aggressive disease, are rarely seen with PBL; Monoclonal serum immunoglobulin and bony lytic lesions with or without hypercalcemia are only detected in rare cases [7],[9]. We propose that, despite this, our patient’s malignancy indeed derived from a mature plasma cell neoplasm. To date only one other case report has been made that describes an association between diagnosed plasmablastic lymphoma arising from apparent plasma cell neoplasm [10].

Cytological findings are elusive in the current literature [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes PBL as a subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, specifically of diffused large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), with morphological features that overlap both myelomas and lymphomas [1],[7],[11] . The most common histological findings are hypercellular specimens with plasmablastic morphological features in the setting of background necrosis [12]. Typical immunophenotype and in situ hybridization (ISH) findings for plasmablastic lymphoma (with prevalence of genotype in parentheses) include CD38 (95.3%), CD138 (91.2%), EBER (70.4%), and MUM1/RF4 (98.8%) [2],[13],[14]. Plasmablastic lymphoma is typically negative for (or rarely shows dim positivity) differentiated B-cell markers to include CD20, CD19, and PAX 5. Lastly, there is strong Ki-67 positivity in aggressive PBL [13],[15]. In a four-case series by Ricker et al., all patients with advanced disease had a Ki-67 proliferation index over 70% [16].

Given the rarity of this malignancy, no standard-of-care treatment regimen has been established [1]. However, proposed treatment regimens follow those established for lymphomas to include CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone) in resource constrained settings. The NCCN guidelines for AID-Srelated B-cell lymphomas (Version 5.2021) recommends the more intense regimen of dose adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, and doxorubicin with boluses of cyclophosphamide and prednisone) [1],[17],[18]. One review suggests an improvement of survival with more aggressive treatments, such as EPOCH [19]. Considering plasmablastic lymphoma’s strong positivity for CD38, the addition of the monoclonal antibody Daratumumab has been used efficaciously in some case reports and has been suggested as an augmentation to EPOCH [16]. This formed the cornerstone of our therapy for the patient presented herein.

Case Report

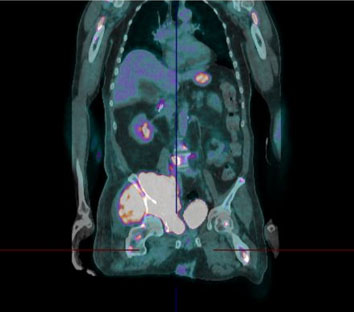

We present a 66-year-old Hispanic man with a history remarkable only for type 2 diabetes and recent duodenal ulcers, who presented with pain in his pelvis and right lower extremity resulting in decreased mobility. Over a matter of weeks, this progressed to severe weakness and sensation loss in his right lower extremity. Associated symptoms included mild night sweats, and weight loss of an unspecified amount. Initial imaging localized a mass to the patient’s right iliac crest and a follow-up positron emission tomography (PET)-computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a highly fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avid osteolytic, hypermetabolic mass centered on the right acetabulum with extramedullary invasion of adjacent soft tissues (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Associated pelvic lymphadenopathy was noted in addition to diffuse osteolytic metastases throughout the axial skeleton from the skull to proximal femurs with inclusion of calvarial and skull base bone lesions, C2 lamina, left sacrum, occipital and frontal bone lesions with possible involvement of the peri-aortic abdominal lymph nodes. Differential prior to biopsy included metastatic sarcoma or multiple myeloma with an aggressive variant of plasmacytoma. A serum protein electrophoresis revealed an M-spike of 0.57 g/dL. Fourth generation HIV antigen-antibody assay and HHV-8 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were both negative with a normal absolute CD4 count of 1052 cells/uL. Notably, the EBV quantitative PCR was 67,600 copies/mL.

Biopsies of the right iliac bone lesion were performed by interventional radiology. Histologic analysis of the lytic lesion in the lateral right iliac wing revealed large, atypical cells with plasmablastic and immunoblastic morphology proliferating in the bone marrow (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated strong EBV positivity by ISH (Figure 4C), strong CD138 and MUM-1 positivity (Figure 4B), dim to variable CD79a positivity, and a Ki-67 proliferation index >99% in the cells of interest. These markers were chosen because of their association with PBL cases. 90% of cases of PBL show CD138 positivity, and nearly 100% of cases show MUM-1 positivity [1]. CD79a is common in all cases of PBL, with 45% positivity in HIV-positive cases and 36% positivity in HIV-negative cases [1]. Ki-67 has a high degree of positivity in all PBL cases, with 90% in HIV-positive cases and 83% in HIV-negative cases [1]. CD20 and PAX-5 were negative. These are markers of mature B-cell neoplasms and are expected to be negative in blastic-type neoplasms [1]. There was a plasma cell clone with a TP53 deletion and (IGH) gene rearrangement, gain of BCL2 and BCL6 genes and MYC amplification. No MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements were seen. A separate bone marrow biopsy, taken later from the right iliac crest, revealed a second population of oval-shaped cells with an eccentric nucleus and clock face chromatin consistent with mature plasma cells (Figure 5). This cell population demonstrated CD138 positivity (15–20% plasma cells) with a kappa restricted clone (Figure 6) and was diffusely EBV negative by ISH (Figure 7). Therefore, the final histopathologic diagnoses were a plasmablastic lymphoma lesion (lateral right iliac wing) and a mature plasmacytoma of the bone marrow (right iliac crest).

The patient was immediately transferred to the oncology ward where therapy was initiated with a steroid lead-in followed by Daratumumab and EPOCH (Table 1). Following the completion of cycle 1, the patient received central nervous system prophylaxis with 15 mg intrathecal methotrexate because of an elevated NCCN-IPI score (National Cancer Consortium Network International Prognostic Index for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma) [18]. The patient was discharged without complication to an acute rehab facility on day eight, hemodynamically stable and afebrile, with a complete blood cell count as the following: White blood cell count: 5.56×109 cells/liter, hemoglobin: 8.5 grams/deciliter, and platelets 148×109 cells/liter.

Unfortunately, at the acute rehab facility, the patient worsened clinically and represented to the ER with altered mental status, neutropenic fever, hypotension and was found to be COVID-19 positive. Blood cultures were positive for drug-resistant pathogens and ultimately the patient developed multi-organ failure and following transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) and succumbed to his illness despite aggressive treatments with empiric antibiotics, vasopressor support, and intubation.

Discussion

This case of HIV-negative, stage IV, PBL with evolution from an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia is a unique presentation with a rare pathogenesis, occurring in about 1% of all B-cell lymphomas [7].

Plasmablastic lymphoma is an aggressive lymphoid neoplasm that represents a type of large B-cell lymphoma that typically arises in immunocompromised patients, most often associated with HIV-positivity [7]. Classically, patients who present with bone-involved PBL are HIV-positive males. In contrast, HIV-negative patients with PBL are typically female, and rarely have bony involvement. Despite these norms, our patient with PBL was an overtly immunocompetent, HIV-negative male, with biopsy-proven bone-involvement. Moreover, the neoplasm found in this patient, by WHO classification guidelines, was determined to be an evolution of an underlying plasmacytoma, which as above, has only been reported once prior in the literature [10].

The histomorphologic differential in this case includes but was not limited to DLBCL, NOS with immunoblastic morphology, DLBCL with partial plasmablastic phenotype, EBV-positive DLBCL, and MYC and BCL2 rearranged large B cell lymphomas with plasmablastic features transformed from follicular lymphoma [7]. The biopsy of the lytic lesion in the right iliac wing was strongly positive for EBV by ISH which is atypical for plasmablastic myeloma and plasmacytoma [10]. Thus supporting the diagnosis of PBL in the lateral right iliac wing lesion and PCM in the EBV negative right iliac crest lesion.

Previous cases of plasmablastic transformation of PBL from plasma cell myeloma (PCM) are usually heralded by a prior diagnosis of PCM. In contrast, for our case, PCM was diagnosed following the initial diagnosis of PBL. Additionally, this patient presented with several clinical features suggestive of myeloma including a monoclonal gammopathy on serum protein electrophoresis, additional lytic lesions on the axial skeleton, and anemia without hypercalcemia or renal impairment.

Though the diagnosis of PBL was initially driven by the strong EBV positivity, subsequent IHC stains, such as the strong CD138 and MUM-1 positivity, further supported this diagnosis. Diffuse and strong MUM-1 is also highly associated with PBL in the context of the other findings [4]. CD79a is positive in 40% of PBL cases [7]. The diagnosis of a PBL in this HIV-negative immunocompetent patient with concurrent PCM is consistent with a PBL arising from a PCM.

In terms of prognosis, it is possible that the high degree of EBV viral load may have contributed to the malignancy of this patient’s disease. Epstein–Barr virus infection occurs in most of the world’s population. The virus lies dormant in the memory-B lymphocyte cell population but, when unchecked by normal immune function, has an association with Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [20]. Our patient was EBV positive with quantitative PCR levels greater than 67,000. Currently literature suggests that EBV-positivity alone is associated with a poorer prognosis for patients with DLBCL. There is not a consensus on a specific viral-load cutoff that could be correlated with disease progression or outcome. However, one study by John Hopkins, quantitative levels of EBV DNA were higher in patients who were HIV-positive and immunocompromised with active disease. The malignancy of the lesion is further supported by a strong Ki-67 of 99%. A series of studies have suggested worse outcomes in patients with Ki-67 expression >80% [2],[21],[22],[23]. This was considered a high-staged lesion (Ann Arbor stage IV), with a poor prognosis. We conjecture that the high level of EBV activity present in the setting of transformation to PBL a contributor to the development of malignancy. This is an area of future work; correlation of EBV viral load to the malignancy of PBL can provide valuable prognostic data to patients in the future.

The patient’s unique treatment regimen was designed considering both the poor prognosis of untreated disease, and the high stage and malignant characteristics of the lesion. The aggression and malignancy of the tumor (EBV-viral load and HIV-negative statuses, in addition to high burden of disease) suggested treatment with a consolidative-guided intensity chemotherapy regimen. We created a unique treatment course of EPOCH for five days with a first-day lead-in with Daratumumab. Daratumumab was selected because of its activity against CD38 positive cells. Details of the regimen are reported in Table 1. Lastly, as previously mentioned, the patient was additionally prophylaxed with 15 mg intrathecal methotrexate because of an elevated NCCN International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) score. The patient had good response to all aspects of the chemotherapy regimen.

Conclusion

This was one of the few presentations in the literature of an HIV-negative man with extranodal plasmablastic lymphoma transformed from a mature plasma cell neoplasm, who was otherwise immunocompetent. Diagnosis was primarily guided by immunohistochemical phenotype, determined to be CD138 and MUM1 positive with negativity for CD20 and PAX-5, in the setting of separate lesions suggestive of clonal plasma cell involvement, positive M-spike, and diffuse lytic bone lesions. The patient was treated with a unique therapy of Daratumumab and EPOCH, and showed adequate tolerance to therapy. Though, sadly, the patient did not fare well, this is an important contribution to body of literature on a very rare disease in an even rarer set patient characteristics. Future work will involve correlation of EBV levels to the prognostication and continual tailoring of chemotherapy regimens. Continual production of case studies describing the presentation of PBL and approaches to treatment are critical to further understanding and improvement of patient outcomes.

REFERENCES

1.

Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood 2015;125(15):2323–30. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, et al. Clinical and pathological differences between human immunodeficiency virus-positive and human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with plasmablastic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51(11):2047–53. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: A new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 1997;89(4):1413–20.

[Pubmed]

4.

Bibas M, Castillo JJ. Current knowledge on HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2014;6(1):e2014064. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Bailly J, Jenkins N, Chetty D, Mohamed Z, Verburgh ER, Opie JJ. Plasmablastic lymphoma: An update. Int J Lab Hematol 2022;44(Suppl 1):54–63. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Pather S, Mashele T, Willem P, et al. MYC status in HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: Dualcolour CISH, FISH and immunohistochemistry. Histopathology 2021;79(1):86–95. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: Evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood 2011;117(19):5019–32. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Loghavi S, Alayed K, Aladily TN, et al. Stage, age, and EBV status impact outcomes of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: A clinicopathologic analysis of 61 patients. J Hematol Oncol 2015;8:65. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Taddesse-Heath L, Meloni-Ehrig A, Scheerle J, Kelly JC, Jaffe ES. Plasmablastic lymphoma with MYC translocation: Evidence for a common pathway in the generation of plasmablastic features. Mod Pathol 2010;23(7):991–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Diaz R, Amalaseelan J, Imlay-Gillespie L. Plasmablastic lymphoma masquerading solitary plasmacytoma in an immunocompetent patient. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2018225374. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, Pileri SA. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: An overview. Pathologica 2010;102(3):83–7.

[Pubmed]

12.

Reid-Nicholson M, Kavuri S, Ustun C, Crawford J, Nayak-Kapoor A, Ramalingam P. Plasmablastic lymphoma: Cytologic findings in 5 cases with unusual presentation. Cancer 2008;114(5):333–41. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Vega F, Chang CC, Medeiros LJ, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas and plasmablastic plasma cell myelomas have nearly identical immunophenotypic profiles. Mod Pathol 2005;18(6):806–15. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Mori H, Fukatsu M, Ohkawara H, et al. Heterogeneity in the diagnosis of plasmablastic lymphoma, plasmablastic myeloma, and plasmablastic neoplasm: A scoping review. Int J Hematol 2021;114(6):639–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Chen BJ, Chuang SS. Lymphoid neoplasms with plasmablastic differentiation: A comprehensive review and diagnostic approaches. Adv Anat Pathol 2020;27(2):61–74. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Armstrong R, Bradrick J, Liu YC. Spontaneous regression of an HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in the oral cavity: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65(7):1361–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Tchernonog E, Faurie P, Coppo P, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: Analysis of 135 patients from the LYSA group. Ann Oncol 2017;28(4):843–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Guidelines, Version 5. 2021. AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2023. [Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf]

19.

Makady NF, Ramzy D, Ghaly R, Abdel-Malek RR, Shohdy KS. The emerging treatment options of plasmablastic lymphoma: Analysis of 173 individual patient outcomes. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2021;21(3):e255–63. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

20.

Kanakry JA, Hegde AM, Durand CM, et al. The clinical significance of EBV DNA in the plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with or without EBV diseases. Blood 2016;127(16):2007–17. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

21.

Castillo JJ, Furman M, Beltrán BE, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: Poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer 2012;118(21):5270–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

22.

Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, et al. HIV-negative plasmablastic lymphoma: Not in the mouth. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2011;11(2):185–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

23.

Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, et al. Prognostic factors in chemotherapy-treated patients with HIV-associated Plasmablastic lymphoma. Oncologist 2010;15(3):293–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the combined efforts of the Hematology/Oncology and Pathology Departments at Brooke Army Medical Center, and the efforts of Dr. Muhammad Pathan at the Veteran’s Affairs Hospital in San Antonio.

Author ContributionsMorgan P Pinto - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Nicholas S Thorneloe - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Mark R Brown - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Molly L Stalons - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Kristin E Stoll - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Allen R Holmes - Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Muhummad Pathan - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Paul A Gonzales - Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2023 Morgan P Pinto et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.