|

Case Report

Primary treatment of malignant retinal detachment caused by choroidal breast cancer metastasis using only systemic chemotherapy and anti-HER-2 therapy

1 Specialist Registrar in Medical Oncology, Tayside Cancer Centre, Ward 32, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, DD1 9SY, Scotland, UK

2 Associate Specialist, Department of Ophthalmology, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, DD1 9SY, Scotland, UK

3 Honorary Senior Lecturer, School of Medicine, University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, DD1 9SY, Scotland, UK

Address correspondence to:

Douglas James Alexander Adamson

Honorary Senior Lecturer, School of Medicine, University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, DD1 9SY, Scotland,

UK

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100119Z10HS2023

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Shareef HEJ, Sharpe G, Adamson DJA. Primary treatment of malignant retinal detachment caused by choroidal breast cancer metastasis using only systemic chemotherapy and anti-HER-2 therapy. J Case Rep Images Oncology 2023;9(1):12–16.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Choroidal metastasis is a disabling complication of several types of common cancer, including breast cancer. Metastases to the choroid may present insidiously but ultimately cause significant visual disturbance and more rarely may result in retinal detachment, causing sudden and profound visual impairment. The usual treatment of choice for choroidal metastases is palliative radiotherapy. External beam radiotherapy to the posterior orbit is often effective in stabilizing and improving the symptoms but it can usually be given only once and carries the risk of cataract induction as a side effect.

Case Report: Here we report using only systemic therapy [chemotherapy and initial dual anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) therapy] to treat a 69-year-old female presenting with newly diagnosed widespread secondary breast cancer, a major symptom of which was visual disturbance related to exudative retinal detachment caused by choroidal metastases. The systemic therapy treated the choroidal metastases effectively and allowed the retinal detachment to improve quickly, and the positive effect of the systemic anti-cancer therapy could be observed directly by serial ophthalmological examination over the first two months of the cancer treatment, allowing earlier detection of treatment response than would normally be seen on routine radiological scanning.

Conclusion: We propose that in selected cases systemic therapy alone may be sufficient initial treatment for choroidal metastases from cancers that are expected to show a marked and relatively rapid response to systemic therapy, such as HER-2-positive breast cancer, allowing radiotherapy to be kept in reserve for further treatment of malignant lesions in the choroid in the future.

Keywords: Breast, Cancer, Choroid, Metastasis

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the commonest sources of ocular metastasis [1] although prevalence may vary depending on which geographical series is examined [2]. The most common site in the eye is the posterior choroid, thought to be more commonly involved because of its vascularity and relatively high blood flow [3], with other sites in the uveal tract such as the iris and ciliary body involved in only about 10% of such metastases. Retinal metastasis caused by systemic carcinoma is reported only rarely and usually by malignant melanoma [4]. Retinal detachment is an uncommon presentation of metastasis from breast adenocarcinoma. Here we describe a case of intra-ocular metastasis from metastatic breast cancer involving the choroid and causing unilateral retinal detachment, which regressed completely following systemic anti-cancer therapy. This case report demonstrates that radiotherapy to the orbit may not always be indicated immediately in cases where systemic therapy is thought likely to be rapidly effective.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman presented with early breast cancer [grade 2 ductal carcinoma, T1 N0 M0; estrogen receptor (ER) 8; progesterone receptor (PgR) 7; HER-2 2+; human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) positive] in 2007, and was treated with a left breast tumor wide local excision and axillary node sampling (0/4 nodes positive); followed by adjuvant radiotherapy to left breast and treatment with ER-blockade.

Nearly 15 years later, at the age of 69 years, she was referred to the oncology clinic after a computed tomography (CT) scan done to investigate breathlessness showed widespread metastatic disease with limited liver metastases, multiple pulmonary nodules, and a large sternal mass.

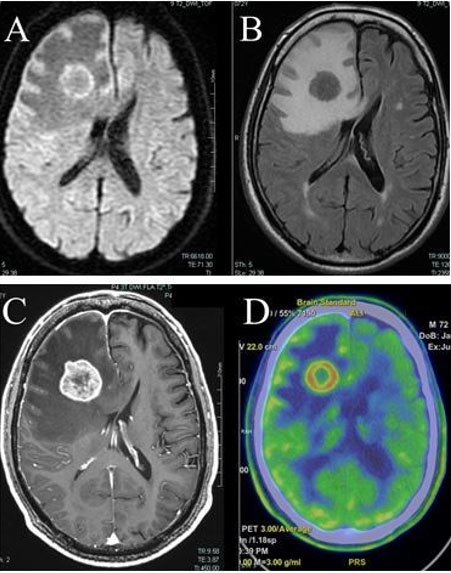

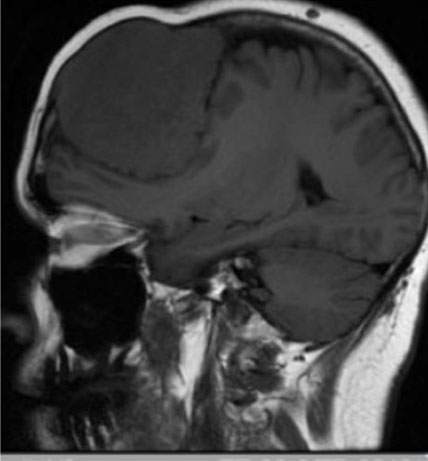

In addition to requiring oxygen, she reported right eye pain, photophobia, and nausea. The patient could only count fingers and recognize faces with the right eye. Computed tomography scan confirmed the presence of hyperdense, almost curvilinear, thickening seen postero-laterally in the right globe suggestive of retinal detachment. An ophthalmic examination revealed a large metastasis in right infero-temporal choroid with associated retinal detachment and no retinal tear (Figure 1). The contra-lateral left choroid was normal and remained so. Biopsy of a left breast mass during presentation with metastatic disease showed grade 3 breast carcinoma of no special type with Allred score ER 8, PgR 0, and HER-2 3+. She was commenced on chemotherapy and dual anti-Her-2 therapy with marked regression of the retinal lesion and improvement in her symptoms. The regimen given was 12 cycles of weekly paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 with Pertuzumab 840 mg intravenous (IV) and Trastuzumab 600 mg subcutaneously. Pertuzumab was discontinued after the first dose because of severe side effects, including gastro-intestinal upset. In total, she had 16 cycles of 3-weekly trastuzumab. Systemic treatment was eventually stopped because of breathlessness and decreasing fitness.

Serum tumor markers (CEA and CA 15-3), which were grossly raised at presentation, fell rapidly and within a few months of her treatment starting. After some treatment, the appearance of the choroidal metastasis improved (Figure 2), she was subsequently assessed as being fit to drive and her breathlessness improved enough to allow her to manage independently and fly to go on holiday. Ten months after treatment commenced tumor markers rose and although CT scan appearances of chest, abdomen, and pelvis were stable, the choroidal metastasis had enlarged and was then treated with palliative radiotherapy.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed neoplastic disease in women and is now considered the most common cause of cancer death in females worldwide [5]. It is expected that up to one-third of patients having been diagnosed with breast cancer will develop metastatic disease[6].

Breast cancer may account for nearly half of the occurrences of ocular metastasis [7] with lung cancer being the next most common at less than 30% [8], although many different primary tumors may cause ocular metastases more rarely [3]. Wiegel and colleagues screened consecutive patients who required irradiation for disseminated breast cancer over 30 months with no ocular symptoms. Six of these patients (5%) were found to have asymptomatic choroidal metastases. In that study, univariate analysis demonstrated a significantly higher risk of choroidal metastases in patients with lung metastases and in patients with brain metastases [9]. The receptor status of the tumors in those six patients with choroidal metastases is not stated, but is interesting to speculate whether HER-2 positivity of the primary is of significance in the development of choroidal metastases, as HER-2-positive breast cancers also have a higher incidence of both lung and brain metastases [10],[11]. In our (relatively stable) population in the east of Scotland, just over 13% of breast cancers at presentation are HER-2-positive, and cancers with a similar receptor profile to this case (ER-positive and HER-2-positive) have a poorer prognosis [12]. Blohmer and colleagues noted a higher incidence of lobular breast cancer causing choroidal metastases, but did not find evidence of association with HER-2 positivity of the primary tumor. Their population was, however, selected only for those who had available records and in addition they had no information on HER-2 status in three-quarters of the patients studied in the control group, which may have affected the conclusions. Their article provides a useful indication of the anatomical distribution of metastases in different orbital sites [13].

Mathis and colleagues provide an excellent overview of this condition, and their article reviews publications describing systemic treatment of choroidal metastases. Most of these reports on systemic therapy and the treatment of ocular malignant lesions, apart from two larger series looking at hormonal-based systemic therapy are, like this one, single case reports only. Mathis et al. make the point that response to systemic therapy may be poorer than the publications suggest, because of positive publication bias leading to the likelihood that descriptions of systemic treatment failures will not be submitted for publication [3].

The most common clinical complaint of patients with ocular metastatic disease is blurred vision, ocular pain, visual field defects, metamorphopsia, floaters, and photopsia [7]. With regard to choroidal metastasis, the typical presentation is a homogeneous creamy yellow choroidal lesion, which is often complicated by secondary exudative retinal detachment [14].

Diagnosis is based on clinical examination supplemented by imaging. Slit lamp biomicroscopy is useful along with imaging studies such as ultrasonography, fluorescein angiography, and CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of orbit. Ultrasonography demonstrates metastatic masses as areas with medium to high internal reflectivity. Fluorescein angiography reveals hyperfluorescence of the mass in the late venous phase. Magnetic resonance imaging may differentiate between diagnosis of breast cancer metastatic disease and choroidal melanoma, since choroidal melanoma demonstrates high signal intensity on T1-weighted image [7]. Computed tomography scan of the brain helps in diagnosing synchronous brain metastasis seen in nearly 25% of cases [15].

Treatment of intraocular metastasis varies and depends on several factors including location, number, and spread of primary disease. Therapeutic options include observation, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, endocrine treatment, resection (only possible with anterior uveal lesions), or enucleation, intravitreal anti-VEGF (Bevacizumab), transpupillary thermotherapy, and laser photocoagulation [15],[16],[17].

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the first and most widely used local treatment against ocular metastatic disease [3]. In our center, we use 20 Gy in 5 daily fractions over one week. The total dose recommended in the literature is not uniform. The overall response rate is 96% and the complete response rate is 61%. Regarding retinal reattachment, the overall reattachment rate is 84% and the complete reattachment rate is 50% [14]. Complications, which to some extent will be dose-related, are expected in nearly 12% of EBRT cases and include cataracts, radiation retinopathy, optic neuropathy, exposure keratopathy, and neovascularization of the iris and rarely narrow-angle glaucoma [15]. Other radiotherapy treatment modalities like plaque brachytherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, cyber knife gamma surgery, and proton beam radiotherapy, are also used to manage ocular metastasis caused by different malignancies [16].

The reported use of anti-HER-2 therapy to treat choroidal metastases is rare [18],[19] and to our knowledge, this is the first case report of initiating treatment with dual anti-HER-2 therapy to treat choroidal metastases with successful results.

Conclusion

This case shows that radiotherapy is not always indicated at the outset to treat choroidal metastases. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case that describes a retinal metastasis complicated by retinal detachment in a patient with newly diagnosed recurrent metastatic breast cancer successfully treated with paclitaxel and dual anti-HER-2 blockade (trastuzumab and initially pertuzumab) leading to complete resolution and improvement in vision. This case shows that the combination of chemotherapy and anti-HER-2 therapy is an effective therapy for symptomatic choroidal metastasis from HER-2-positive breast cancer. Systemic therapy was used as there was also extensive metastatic disease affecting other organs, otherwise a local treatment using radiotherapy alone would have been more appropriate. The choroidal metastasis responded quickly with resolution of the visual symptoms and, in addition, serial ophthalmological examinations provided reassurance and early indication of good treatment efficacy and tumor response, quicker than would normally be possible with standard radiological imaging of metastatic disease as the ocular tumor could be directly visually assessed. Systemic anti-cancer therapy alone may therefore be used to treat choroidal metastasis in such cases, to allow radiotherapy to be kept in reserve for treatment failure. The best cases for this approach would be in patients who have a high chance of response to systemic therapy (e.g., HER-2-positive breast cancer) and for whom systemic therapy is indicated anyway (e.g., those with metastatic disease elsewhere and who are fit for systemic therapy). There is, however, a risk to using systemic therapy alone when choroidal metastases are present, as vision may deteriorate further before systemic treatment failure is recognized—although frequent ophthalmological examination may give an early warning of lack of treatment response in such cases.

REFERENCES

1.

Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology 1997;104(8):1265–76. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Kang HG, Kim M, Byeon SH, et al. Clinical spectrum of uveal metastasis in Korean patients based on primary tumor origin. Ophthalmol Retina 2021;5(6):543–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Mathis T, Jardel P, Loria O, et al. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of choroidal metastases. Prog Retin Eye Res 2019;68:144–76. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Shields CL, McMahon JF, Atalay HT, Hasanreisoglu M, Shields JA. Retinal metastasis from systemic cancer in 8 cases. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132(11):1303–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Lima SM, Kehm RD, Terry MB. Global breast cancer incidence and mortality trends by region, age-groups, and fertility patterns. EClinicalMedicine 2021;38:100985. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Dogan S, Andre F, Arnedos M. Issues in clinical research for metastatic breast cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2013;25(6):625–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Georgalas I, Paraskevopoulos T, Koutsandrea C, et al. Ophthalmic metastasis of breast cancer and ocular side effects from breast cancer treatment and management: Mini review. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:574086. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Arepalli S, Kaliki S, Shields CL. Choroidal metastases: Origin, features, and therapy. Indian J Ophthalmol 2015;63(2):122–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Wiegel T, Kreusel KM, Bornfeld N, et al. Frequency of asymptomatic choroidal metastasis in patients with disseminated breast cancer: Results of a prospective screening programme. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82(10):1159–61. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(20):3271–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Wu Q, Li J, Zhu S, et al. Breast cancer subtypes predict the preferential site of distant metastases: A SEER based study. Oncotarget 2017;8(17):27990–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Purdie CA, Baker L, Ashfield A, et al. Increased mortality in HER2 positive, oestrogen receptor positive invasive breast cancer: A population-based study. Br J Cancer 2010;103(4):475–81. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Blohmer M, Zhu L, Atkinson JM, et al. Patient treatment and outcome after breast cancer orbital and periorbital metastases: A comprehensive case series including analysis of lobular versus ductal tumor histology. Breast Cancer Res 2020;22(1):70. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Rosset A, Zografos L, Coucke P, Monney M, Mirimanoff RO. Radiotherapy of choroidal metastases. Radiother Oncol 1998;46(3):263–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Nirmala S, Krishnaswamy M, Janaki MG, Kaushik KS. Unilateral solitary choroid metastasis from breast cancer: Rewarding results of external radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther 2008;4(4):206–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Haidar YM, Korn BS, Rose MA. Complete regression of a choroidal metastasis secondary to breast cancer with stereotactic radiation: Case report and review of literature. J Radiosurg SBRT 2013;2(2):155–64.

[Pubmed]

17.

Fenicia V, Abdolrahimzadeh S, Mannino G, Verrilli S, Balestrieri M, Recupero SM. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the successful management of choroidal metastases secondary to lung and breast cancer unresponsive to systemic therapy: A case series. Eye (Lond) 2014;28(7):888–91. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Wong ZW, Phillips SJ, Ellis MJ. Dramatic response of choroidal metastases from breast cancer to a combination of trastuzumab and vinorelbine. Breast J 2004;10(1):54–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

19.

Alzouebi M, Ramakrishnan S, Rennie I, Salvi S. Use of systemic therapy in the treatment of choroidal metastases from breast cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2013009088. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

We thank James Talbot and the team of the Ophthalmic Imaging Department and Medical Photography at Ninewells Hospital for expertise in producing the photographs.

Author ContributionsHala Elnagi Jadelseed Shareef - Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Graeme Sharpe - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Douglas James Alexander Adamson - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the late patient’s next-of-kin for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2023 Hala Elnagi Jadelseed Shareef et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.